Canada tax agency reveals secret study linking home prices to millionaire migration, five years after freedom-of-information request

- The 1996 study found rich migrants made more than 90 per cent of luxury purchases in two Vancouver municipalities while declaring refugee-level incomes

- A freedom-of-information expert said the study could have swayed the city’s notoriously unaffordable housing market, and delaying its release was a ‘tragedy’

The response to the South China Morning Post’s request, lodged on August 30, 2016, arrived by mail this August 17, a delay that a freedom-of-information expert called a “tragedy” and “troubling”, given the importance of the material.

The documents confirm the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) knew 25 years ago that wealth migration and foreign money were playing a vast role in Vancouver’s luxury housing market, and that government millionaire migration schemes appeared connected to systematic tax abuse, with participants declaring refugee-level incomes.

But the process was allowed to continue for decades before the lucrative immigration programmes behind the phenomenon were halted in recent years, for the reasons identified by auditors so long before.

The programmes were dominated by Hongkongers and Taiwanese in the 1990s, then mainland Chinese millionaires from about 2001.

It is the first time the CRA has acknowledged the existence of the 1996 study, which a CRA whistle-blower said was covered up then ignored by bosses.

This triggered the access to information and privacy (ATIP) request for information and communications about the study.

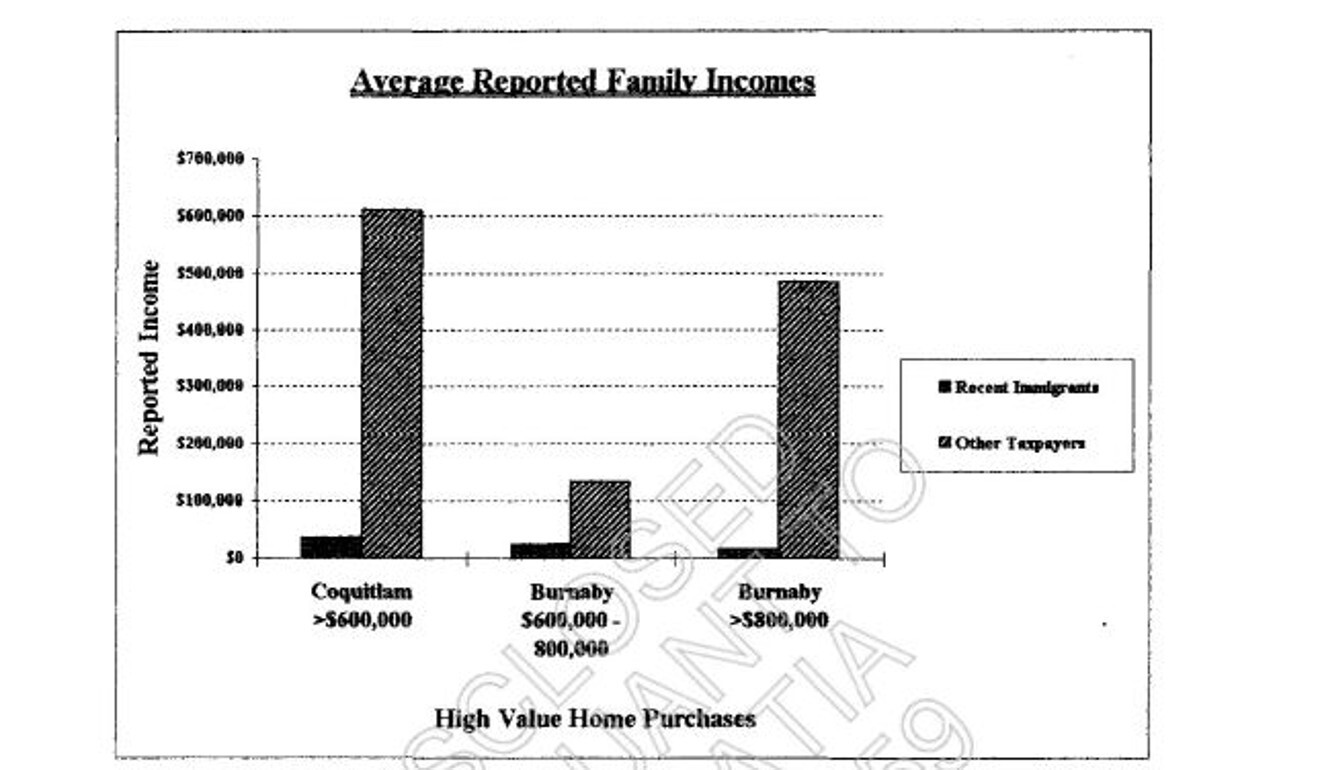

The study found rich new immigrants made more than 90 per cent of high-value home purchases in which buyers were identifiable in the metro Vancouver municipalities of Burnaby and Coquitlam, but were declaring only tiny global incomes.

For example, new immigrant buyers of the most expensive category of homes in Burnaby declared average annual incomes of C$16,430 (US$12,950). Long-term Canadian residents making such purchases declared incomes 16 times higher.

Read the SCMP’s original 2016 investigation into secret CRA housing study

Spreadsheets in the ATIP response list dozens of top-end home purchases by immigrant buyers, including one who bought a Burnaby home for C$2.88 million (US$2.27 million) and declared total global income of C$174 (US$137).

The more expensive the purchase by a new immigrant, the less income, on average, they declared, according to the spreadsheets.

The study was marked as a confidential and a “protected” document, a classification that the material is expected to “cause injury to an individual, organisation or government” if compromised.

The research was triggered by the auditors’ concerns about tax cheating under Canada’s Immigrant Investor Programmes (IIP), the whistle-blower previously said.

But instead of being curtailed as a result of the auditors’ findings, the lucrative schemes would become the world’s most popular millionaire migration vehicles over the next two decades, bringing about 200,000 wealthy newcomers to Canada.

The two government immigration schemes that fuelled the process were shut down or suspended in recent years, after official reports found chronically low tax receipts from participants, in keeping with the auditors’ concerns decades earlier.

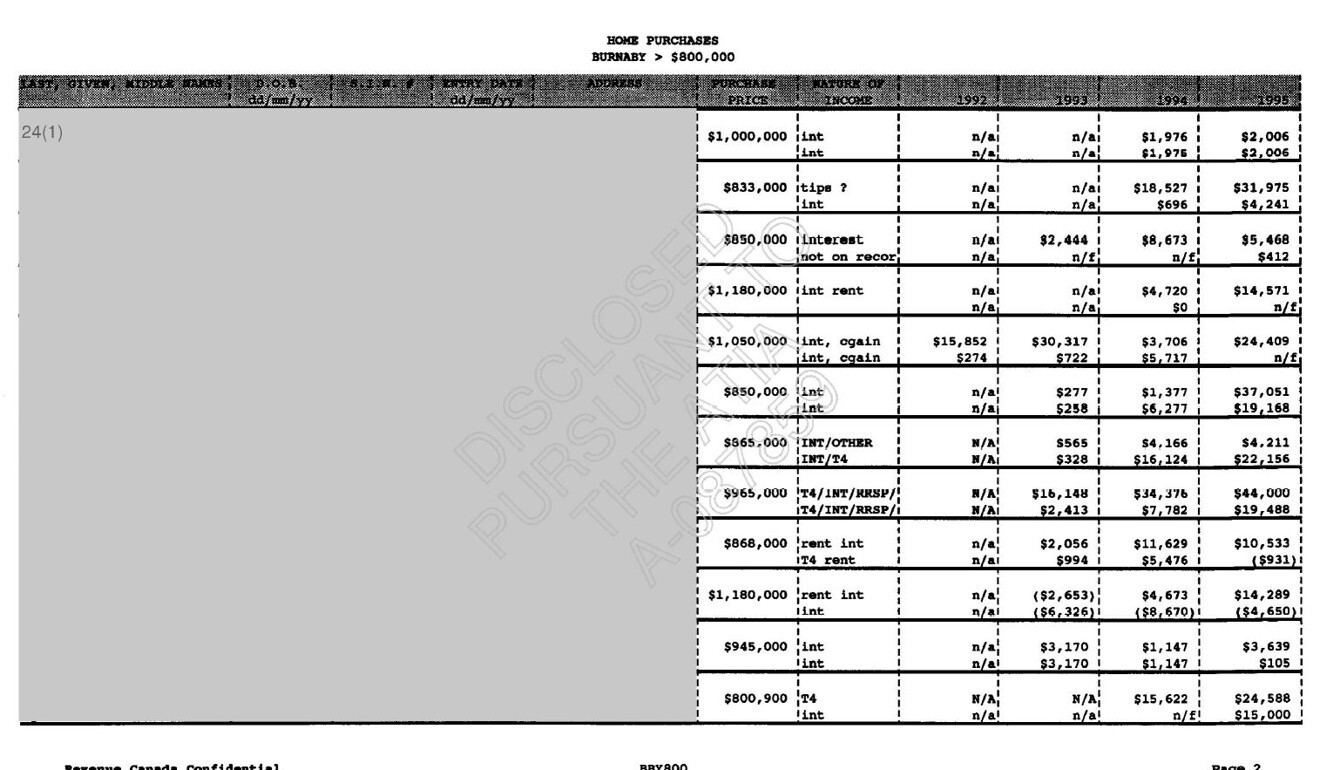

The spreadsheets provided via ATIP list “high-value home purchases” by recent immigrants, along with their declared incomes, although their names and identifying personal details are redacted.

Dino Altoe, the auditor behind the study, said in a memo at the time that the price-income gap was “an obvious large discrepancy”.

“[Based] on the lifestyle and average age of these taxpayers, it is likely that many of these new Canadians still have active business activities, but are not reporting all their sources of income,” Altoe wrote to John Fennelly, at the International Tax Directorate in Ottawa, in a memo dated October 1, 1996. The memo was released in the ATIP response, but had previously been provided by the Post’s whistle-blower, who requested anonymity.

Sean Holman, a journalism professor at Calgary’s Mount Royal University and an expert on Canada’s ATIP system, said the massive delay in producing the material was made worse by the important role housing affordability has played in a series of elections in British Columbia and Canada since 2016.

If this audit had been made available at the time, as opposed to government keeping it secret so long … then maybe we would have had a completely different story about home prices in Vancouver than we have right now

He said he did not know if any ATIP request had taken longer to fulfil, but five years was “definitely at the outer limit”; ATIP officers sometimes warn that requests could take decades to fulfil unless they are modified.

“If this audit had been made available at the time, as opposed to the government keeping it secret so long … then maybe we would have had a completely different story about home prices in Vancouver than we have right now,” said Holman. “That’s the really troubling thing about it.”

According to the annual Demographia report by the Urban Reform Institute think-tank, Vancouver is the second-most unaffordable city among 92 major metropolitan markets in eight countries around the world, with a price-to-income ratio of 13. Only Hong Kong, where median prices are 20.7 times greater than the median income, is ranked more unaffordable.

Holman called the ATIP delay a “dramatic demonstration” of how the system could obstruct transparency, rather than enhance it.

The 2016 CRA whistle-blower could no longer be contacted. Nor could Altoe, whose CRA email address is no longer active.

Discussions about secret study went to the top

The CRA’s ATIP response consists of a single 85-page PDF document on a DVD.

In addition to the study’s redacted spreadsheets, the response includes Altoe’s memo and a two-page data summary for Fennelly, both of which were provided in full, having already been published by the Post.

Emails in the response meanwhile reveal that the then director general of the CRA, Susan Betts, was heavily involved in discussions about the material, and personally approved the CRA’s responses to the Post’s 2016 story.

The next day, she held a meeting with Altoe and others to discuss the 1996 study.

However, Betts’ lengthy emails to other top CRA officials and public relations managers about the investigation are almost entirely redacted. Betts has since left the CRA and is now a senior economist with the International Monetary Fund.

Contacted in Washington, Betts said last week that she could not recall the 1996 study, or how it was handled in 2016.

“That’s a long time ago. I don’t really remember,” she said, declining to comment further.

Thirty-nine pages of the response relate mostly to the August 2016 discussions about how to respond to the Post’s report and inquiries. At the time, the CRA refused to comment on the authenticity of the documents.

But the study had already been circulating among auditors earlier that year, the ATIP response shows.

Canada's millionaire migrants earn less than refugees, so why bother with wealth migration?

In late 2015 and early 2016, the CRA’s approach towards Vancouver’s housing market and possible tax evasion by foreign-earning purchasers had been under intense media scrutiny, and pressure was mounting within the agency to crack down, emails in the ATIP response show.

“You are all aware of the ongoing high-profile of the foreign investment/real estate file in our Region,” wrote Tim Philps, a top CRA manager, in an email to Pacific region auditors in December 2015. “There is an increasing urgency for us to tangibly demonstrate progress.”

[Based] on the lifestyle and average age of these taxpayers, it is likely that many of these new Canadians still have active business activities, but are not reporting all their sources of income

Philps began recruiting auditors to target the “real estate issue … from a new and creative perspective”.

Altoe volunteered to help screen possible audit targets. In a series of January 2016 emails, he alerted colleagues to the existence of the investigation, saying he had found hard copies of the material that he thought had been destroyed.

He offered to “help out in any way”, saying he would scan copies of the study. “THANKS A LOT for this information,” responded Dal Jawandha regional director of the CRA’s underground economy programmes.

Altoe would eventually pull out of the screening sessions, but offered to “help out on a strategic basis”.

Email exchanges about the study are otherwise heavily redacted, so it is not clear how the material was received in early 2016. But at the time it was conducted, the study was never acted upon, the whistle-blower previously said.

In a single 1996 email, Altoe says he tells Fennelly how his team tried to use the study’s findings to target people for world-income audits, but the explanation itself is entirely redacted.

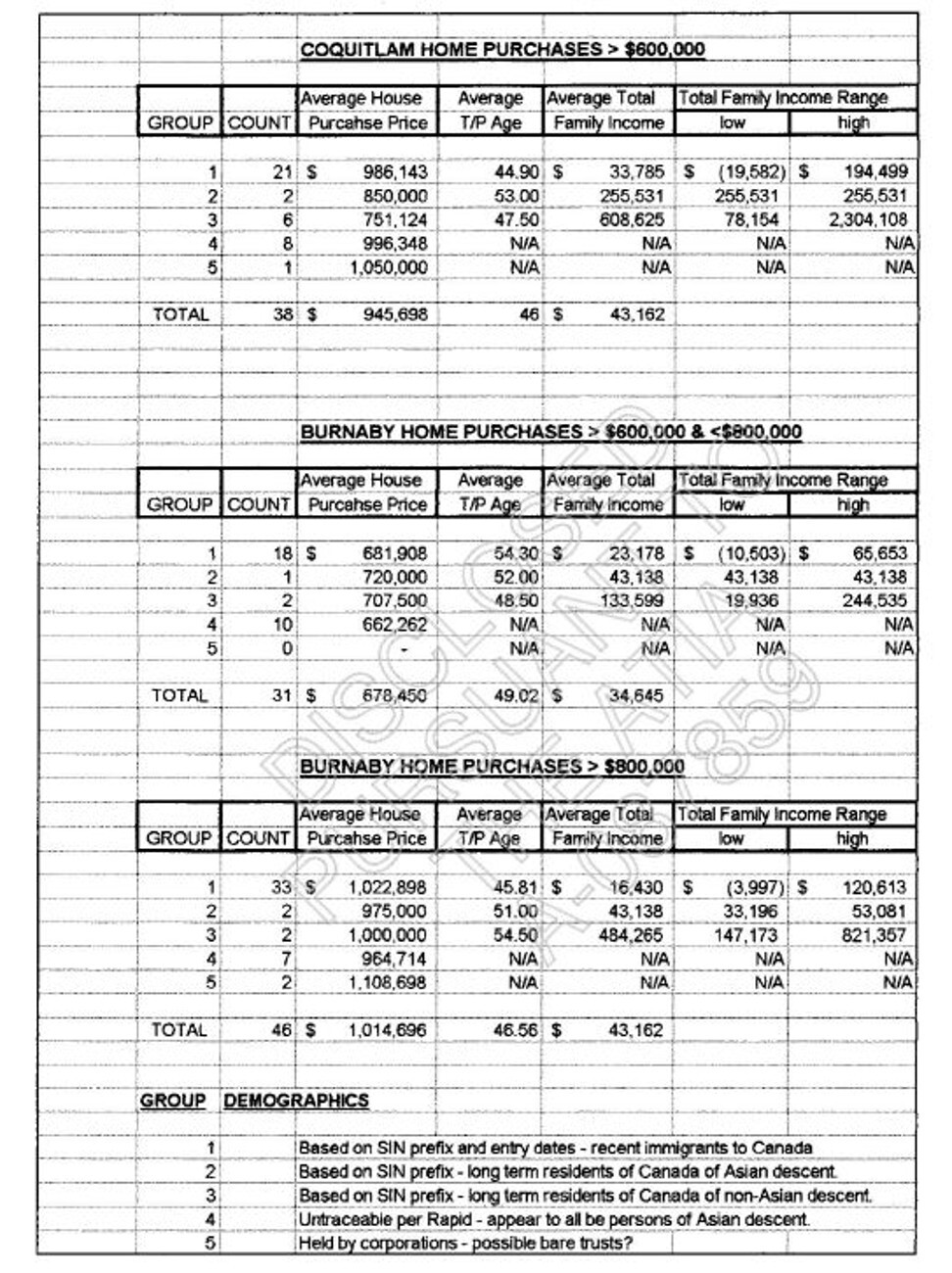

The study’s spreadsheets are divided into three categories: purchases in Burnaby for more than C$800,000 (US$630,000), Burnaby purchases between C$600,000 (US$470,000) and C$800,000, and purchases in Coquitlam for more than C$600,000. A date range is not listed, but the whistle-blower said the study included all purchases made in a two-month period of 1994.

That year, the average purchase price of a home in Burnaby was C$230,473 (US$181,725, and C$213,235 (US$168,135) in Coquitlam, according to Statistics Canada.

The spreadsheets in the ATIP response are anonymised, but the Altoe’s summaries make it possible to determine which of the Burnaby buyers were recent immigrants, and which were long-term residents. The summaries divide long-term residents into people of Asian and non-Asian descent.

Of the 46 buyers for C$800,000 or more in Burnaby, the CRA could identify 37 by name. Thirty-three were recent immigrants, who declared household global incomes averaging a mere C$16,430 in 1994, a small fraction of the C$263,701 (US$207,940) average income declared by long-term residents.

They arrivals included the buyer of a C$1.18million (US$930,000) home who declared negative C$3,997 (US$3,150) of income in 1994, the lowest in the category. The highest income declared by an immigrant buyer was C$120,613 (US$95,105), by a person who bought a home for C$1.55 million (US$1.22 million).

The most expensive Burnaby home in the study, bought for C$2.88 million (US$2.27 million), went to a recent immigrant who declared global income of C$174 (US$137) in 1994 and C$168 (US$132) in 1995.

In the C$600,000-C$800,000 Burnaby category, there were 243 buyers, of whom only four were long-term Canadian residents, according to Altoe’s memo.

The spreadsheets list 31 randomly selected purchases, 21 of which had identifiable buyers. Eighteen were recent immigrants whose average declared income was C$23,178 (US$18,273), compared to C$103,448 (US$81,557) declared on average by long-term residents.

Altoe’s summary says the study found 38 Coquitlam home purchases for more than C$600,000, of which 29 had identifiable buyers. But the spreadsheets only show a total of 33 purchases, making it difficult to determine all of the buyers who were recent immigrants.

The Coquitlam buyer summary lists average recent immigrant income as C$33,785 (US$26,635), compared to C$520,351 (US$410,235) for long-term residents, although this is skewed high by the study’s highest earner, who declared C$2.3 million (US$1.8 million) of income.

By contrast, the lowest earner in the whole study was a recent immigrant who declared a loss of C$19,582 (US$15,438) in 1995, the year after buying a Coquitlam home for C$1.178 million (US$930,300).

Leak reveals secret tax crackdown on foreign-money real estate deals in Vancouver

The spreadsheets do not identify the migration schemes used by the buyers, but Altoe referred to the study as “research on immigrant investor home purchases”.

Canada’s federal IIP and Quebec IIP became the most popular millionaire migration schemes in the world. From 1986 to 2014, the twin schemes brought 190,487 wealthy immigrants to Canada, an estimated 120,000 of whom moved to Vancouver.

These included a majority of Quebec IIP migrants, who were not required to live in the French-speaking province.

The federal IIP was shut down in 2014. The Quebec IIP has been suspended and is currently under review until 2023. Upon suspension in 2019 it had an annual quota of 1,900 immigrants, of whom 1,200 could be of any one nationality. Chinese nationals have historically made up a bulk of Canada’s IIP and QIIP applicants.

The two schemes effectively allowed rich applicants to buy permanent residency in Canada, in exchange for them granting interest-free loans to the federal or Quebec governments. Under their most recent iterations, the QIIP required applicants to be worth at least C$2 million (US$1.58 million), while the federal IIP required applicants to be worth C$1.6 million (US$1.26 million). Applicants would have to loan C$800,000 under the federal IIP and C$1.2 million under the QIIP.

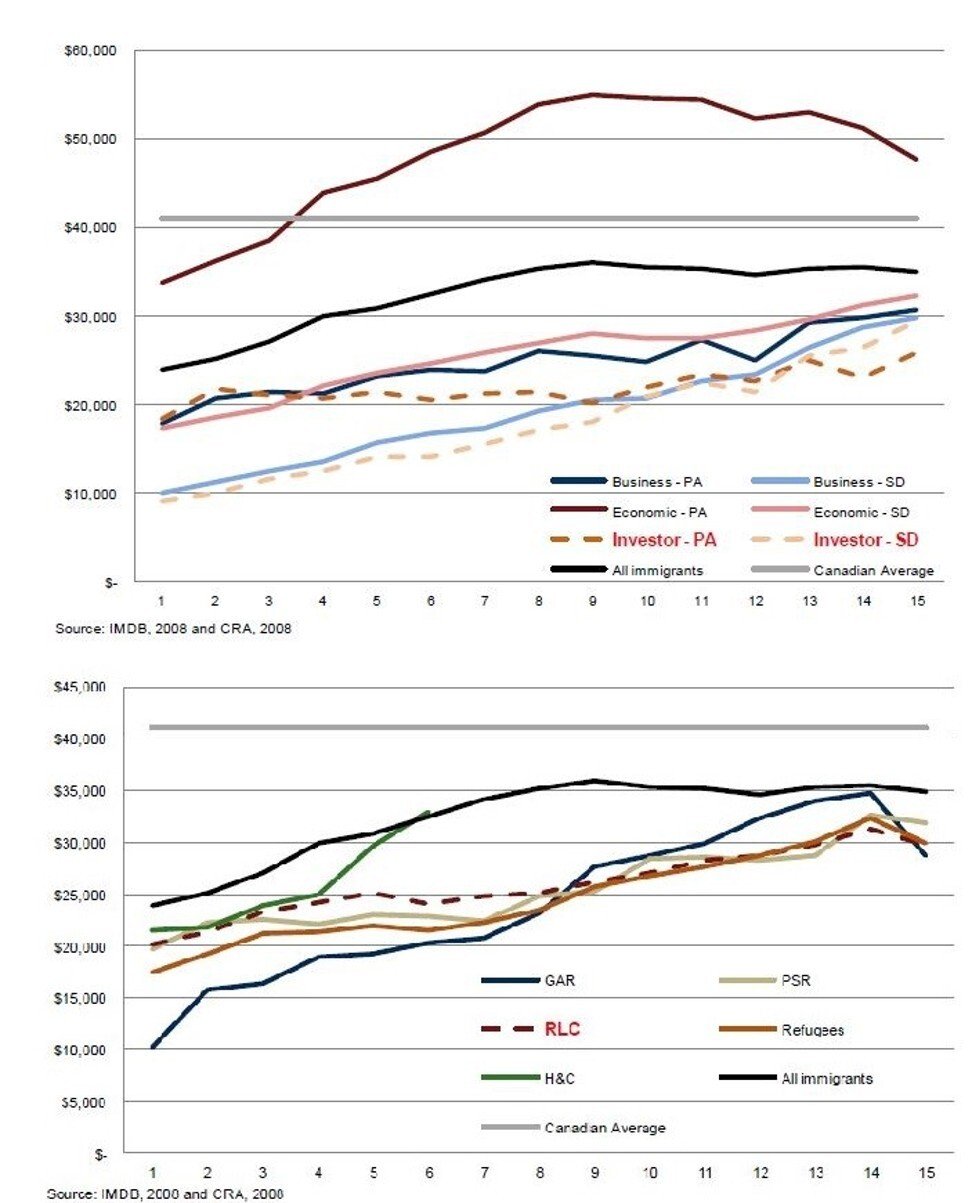

When it shut down the federal IIP in 2014, Canada’s government said the income tax paid by an investor migrant over 20 years was, on average, C$100,000 (US$78,800) less than the tax paid by a live-in carer, and C$200,000 (US$157,600) less than that paid by a skilled worker.

‘You shouldn’t have to wait for someone to leak it’

The ATIP request had gone unanswered for three years when CRA access-to-information manager Denis Roussel phoned in mid-2019 to confirm whether the material was still wanted.

After another year passed, Roussel said the request was still in progress.

On July 28, 2021, Roussel called to say the material was finally ready, and it arrived by mail 20 days later.

Roussel acknowledged the five-year response time was “not normal”. All of the staff who started working on the file had since changed jobs, he said.

Canada tax agency wants ‘blood’: not from global-income cheats, but from leaking auditors

“I think it just went from one person to the other,” he suggested.

He said multiple inquiries had been lodged about the 1996 study. “I think it was a tricky subject back then,” he said.

In a letter that accompanied the DVD, Roussel wrote that the extensive redactions were variously justified on the grounds that the information was personal, that its release could hinder investigations, or for security reasons.

In a report to parliament, the CRA said it received 2,864 new ATIP requests in the year to March 31, 2020. It carried over 1,187 earlier requests – including the Post’s – and fulfilled or closed 2,731, of which 220 took longer than one year to complete.

Holman decried the length of time taken to fulfil many information requests, and the extensive redactions seen on many responses, arguing that the ATIP system was designed to “conform to the contours of existing secrecy” in government, rather than challenging it.

“This isn’t just a story about how freedom of information is broken. It’s a story about how transparency in general is broken,” Holman said.

“This kind of audit should be in the category of ‘readily available’. It should be in the category of ‘released as a matter of course’. You shouldn’t have to wait for it. You shouldn’t have to wait for someone to leak it. That’s what’s outrageous.”