Addicted: Meth fuelling petty and violent crime in Edmonton

This is part two of a five-part series examining methamphetamine in Alberta’s capital city.

Article content

Just before noon on Sept 17, 2018, Mario Bigchild walked into a Husky gas station on 107 Avenue and leaped over the counter. He pulled a knife, demanded cash from the terrified clerk, and fled with $500.

The robbery was the beginning of a 20-hour crime spree that ended with Bigchild repeatedly thrusting a knife into the chest of a 19-year-old University of Alberta student who was waiting for an LRT train. The student likely would have died had it not been for the quick actions of three bystanders — a doctor, a nurse and a Good Samaritan who intervened in the attack.

Bigchild later admitted he committed the crimes while on a 10-day methamphetamine binge. In a police interview after his arrest, Bigchild was disoriented and incoherent. He claimed he’d attacked the student because he believed he was a “predator” based on “a look in a nearby woman’s eyes.”

Bigchild, 26, had no criminal record before that day. He will be sentenced Oct. 8.

Meth does not inherently make people violent, or more prone to committing crimes. Nevertheless, in Edmonton, the drug has been a precipitating factor in crimes ranging from hand dryer thefts to homicides. Police and courts continue to grope toward a coherent strategy for dealing with the problem, with mixed results.

‘It takes hold when it’s cheap’

Western Canada’s meth problem took a backseat following the work of the 2006 Alberta task force. The year after Colleen Klein’s panel tabled its ill-fated report with 83 recommendations that were not acted on, The Globe and Mail ran a story which found the Prairie provinces were “finding solutions” to the meth problem. Simply put, meth just wasn’t as big a concern as it had been.

-

Addicted Part One: How meth hooked Edmonton — again

Addicted Part One: How meth hooked Edmonton — again -

Addicted Part Three: How meth takes a toll on Edmonton's health system and devastates users

Addicted Part Three: How meth takes a toll on Edmonton's health system and devastates users -

Addicted Part Four: How meth erodes Edmonton-area families and communities

Addicted Part Four: How meth erodes Edmonton-area families and communities -

Addicted Part Five: How Edmonton could solve its meth problem

Addicted Part Five: How Edmonton could solve its meth problem - Read our entire Addicted series on meth in Edmonton

The Globe gave some credit to organized opposition to the drug — some believed advertising campaigns warning youth about meth’s physical and mental devastation were particularly effective. Probably the bigger factor, though, was the economy. Alberta was still booming in 2007 — the peak before the 2008 financial crisis — and many drug users had money for more expensive stimulants like cocaine. Users seemed to be willing to pay more for a drug that produces a similar high without meth’s stigma.

“(Crystal meth) is still brutal,” MLA and former crystal meth task force member Mary Anne Jablonski told The Globe at the time. “But it’s not as big as we thought it would become.”

Within a decade, meth’s popularity was on the rise again.

Police Chief Dale McFee is a big part of the reason Edmonton is talking about meth in 2020. Since becoming police chief in February 2019, he’s brought up meth at almost every opportunity. Late last year, he outlined what he called a “bold” plan to reduce meth-related calls for service by 20 per cent through partnerships with health-care providers.

For 26 years, McFee served as a police officer in Prince Albert, Sask., including a nine-year stint as chief. Saskatchewan has grappled with meth for just as long as Alberta — former Saskatchewan premier Lorne Calvert called it Western Canada’s “common curse.”

“As soon as I came here, just looking at our stats — very similar to what I was seeing in Saskatchewan,” McFee said in a February interview. “This has been hitting the West for a few years now, so it wasn’t a surprise when I saw it. What was a surprise was just how much there was.”

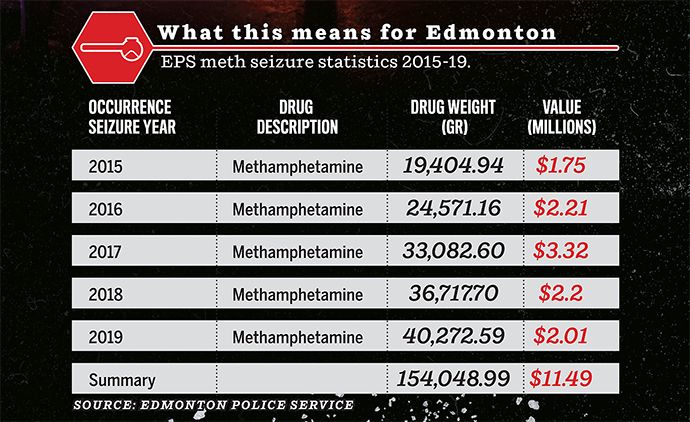

In 2015, Edmonton police seized 19,404 grams of meth valued at $1.75 million. Last year, they seized 40,272 grams worth more than $2 million. During that time, the price dropped. A gram of meth in 2015 ran $90, according to police, compared to about $50 in 2019.

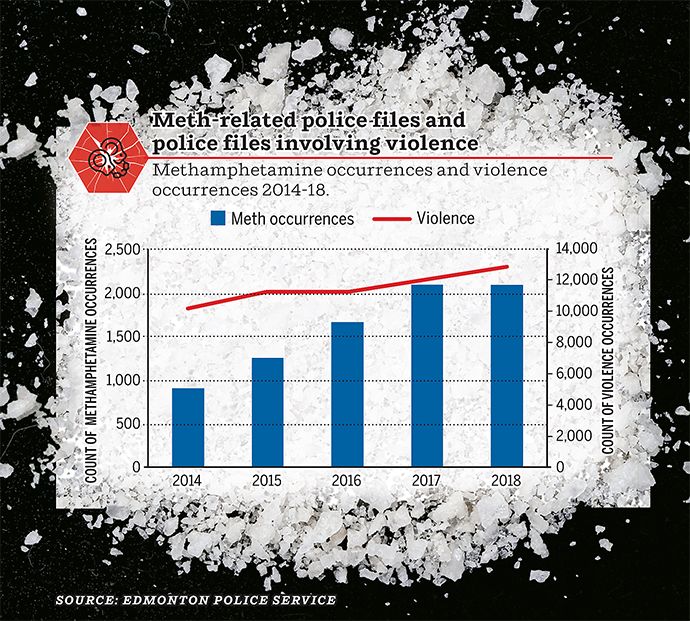

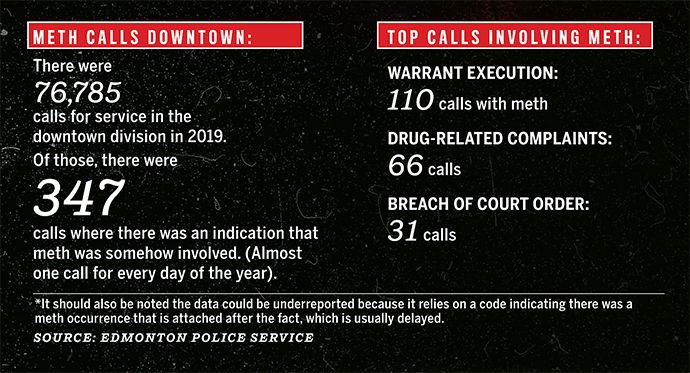

Meth-related police calls, meanwhile, have surged. Between 2014 and 2018, calls involving meth doubled from 903 a year to more than 2,085. Violent crime increased as well (to 12,863 incidents from 10,220 incidents), as did flights from police (to 600 from 233), which McFee attributes in part to meth.

Police have also linked a range of increasingly brazen property crimes to increased meth usage. Liquor store thefts went through the roof last year, along with thefts of catalytic converters and even Dyson-brand hand dryers, which contain valuable metals.

Meth is also common in police interactions that turn violent. In January, Alberta’s police watchdog cleared three officers in the death of 30-year-old Matt Dumas, a suspected drug dealer who shot at police after officers boxed in his Mercedes outside an Edmonton McDonald’s. Two teenage girls in the car were miraculously uninjured when police opened fire. An autopsy revealed Dumas had meth in his system.

“Methamphetamine is our Number 1 problem,” Alberta Serious Incident Response Team (ASIRT) executive director Susan Hughson said during a January press conference.

“It is one of those drugs that causes impulsive and irrational decisions, and that appears to be part of what took place in (the Dumas) case,” Hughson said.

For McFee, Edmonton’s current meth problem is a question of simple economics. “Cheap,” he says when asked about meth’s recent resurgence. “It takes hold when it’s cheap.”

McFee has stressed that police can’t tackle the meth problem alone, and that the response can’t be enforcement only. “It’s gotta be a public health and a police response at the same time,” he said. “It’s one thing to get the people that are selling it, that are pushing it, moving it into the city … but it’s another thing to make sure that we’re dealing with the addict, the vulnerable person on the other end, and trying to get them into treatment.”

From cartel to the streets of Edmonton

Police believe most domestically-produced meth comes from “superlabs” in B.C. and Ontario. Precursor chemicals like ephedrine and pseudoephedrine, which traditionally fuelled small-scale meth labs, are now heavily regulated.

Increasingly, Canada’s meth is coming from Mexico, where cartels are manufacturing the drug with chemicals imported from China and India, according to an EPS briefing paper. Meth seizures at the U.S.-Canada border rose 333 per cent between 2017 and 2018. Police believe cartels are selling more and more meth in an attempt to offset declining marijuana sales.

“The Mexican cartels are involved in all sorts of stuff. They’re very good at what they do,” said Kelly Sundberg, a Mount Royal University professor formerly with the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA). Meth is relatively compact and difficult to detect, he said. “It gets smuggled in all sorts of ways.” Loads of drugs “come up in food shipments, they come up in shipments of goods in trucks.”

Another route is the mail. In March, the Winnipeg Free Press reported that between 2017 and mid-2018, the CBSA made 448 postal seizures containing meth. The highest number of shipments came from the Netherlands, while the largest overall quantities were shipped from Mexico.

Once in Canada, meth is typically trafficked by organized crime groups or independent distributors. The latter are usually referred to as “dial-a-dope” rings, said Guy Pilon, a sergeant in the EPS drug and gang enforcement section.

The lowest employee in a dial-a-dope ring is the dialler, who takes calls and travels to meet prospective clients. Above him is the “food boss,” who supplies a handful of diallers and usually handles multiple ounces or even pounds of product, said Pilon. At the top of an organization is a “boss,” who liaises with larger-scale distributors. In Alberta, the starting point sentence for meth trafficking is three to four-and-a-half years in prison, depending on the amounts sold.

At the street level, meth is typically sold by the gram. Grams contain 10 “points,” which are good for a handful of hits depending on the quality.

Like so many areas of life, COVID-19 has taken a sledgehammer to illicit drug markets.

Before the pandemic, meth was “on sale,” said Pilon, going for $20 to $30 a gram. Now, that much typically buys a single point. Local meth supplies seem to have “dried up,” Edmonton outreach worker Mark Cherrington said in a Sept. 1 post to Twitter.

On top of that, meth supplies are increasingly contaminated with other substances, including deadly opioids. British Columbia recently moved to expand access to pharmaceutical alternatives to street drugs in a bid to reduce overdose deaths. B.C. provincial health officer Dr. Bonnie Henry blamed increased drug toxicity in part on COVID-19-related border closures.

Random violence

The relationship between meth and violent crime is murky, a 2013 study in the Journal of Drug Issues found. The drug most frequently implicated in homicides is alcohol. Harm reduction advocates have repeatedly pushed back against the idea of meth users as drug-crazed “zombies.”

Still, meth has been an ingredient in a number of high-profile Edmonton criminal cases, several involving chilling acts of random violence.

Edward Kyle Roberts, a man who admitted to brutally killing an elderly couple in their home, was in a state of drug-induced psychosis likely linked to his meth use.

Another man, Dakota Cappo, was sentenced to 14 years for lighting a deadly fire in the stairwell of his girlfriend’s apartment after smoking methamphetamine.

Jordan Cushnie, who admitted to killing flower shop owner Iain Armstrong during a 2018 robbery at Southgate Centre, had also been using meth the day of the crime. Notably, Roberts, Cushnie, and Bigchild — the man who stabbed the student at the LRT station — were all living on the streets when they committed their crimes.

Countless other cases involving meth receive far less attention.

How the Canadian justice system approaches illicit drug use is changing rapidly. In July, the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police (CACP) endorsed decriminalization of personal possession — meaning the drugs remain illegal, but the penalty would be reduced from a criminal charge to a fine or other type of sanction.

The following month, the Public Prosecution Service of Canada, which prosecutes offences under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, made changes to its deskbook, which sets out principles for prosecutors to follow. The new directive urges prosecution in only the most serious drug cases, such as those that put public safety or children at risk. In all other cases, federal prosecutors are urged to look at alternatives such as moving the case to drug treatment court.

Keeping addicts out of prison

Edmonton’s drug treatment court launched in 2005 with funding from the federal government. The idea is to keep non-violent offenders whose crimes were driven by addiction out of prison.

Drug court participants are subject to random drug tests, as well as a variety of incentives and sanctions depending on their performance. It takes at least a year to “graduate” from the program, which meets weekly in room 267 of the Edmonton provincial courthouse. Attendees sit on wooden benches in the gallery, and come up one at a time to share their stories with the court. Compared to a regular court, drug treatment court is bright, even bubbly. Judges and attendees are often on a first-name basis. Applause from court staff and families in the gallery is common.

Alberta’s UCP government has made drug treatment court a major part of its addictions and mental health strategy, but there are still just 80 drug court spots per year between Edmonton and Calgary, even after the UCP government doubled funding. In June, the government announced plans to establish drug courts in five smaller centres, including Red Deer.

There’s also mental health court, which meets three days each week in courtroom 357. A pair of provincial court judges — Larry Anderson and Renee Cochard — established the court in 2018 to deal with the high volume of mentally ill and addicted people in Alberta’s legal system.

While mental illness is the one thing that unites defendants in mental health court, another common thread is methamphetamine.

“A lot of the files now have meth as a common denominator,” said Mark Grotski, a defence attorney of more than 30 years who represents clients in mental health court.

Postmedia sat in on the court on the morning of Jan. 29. Within an hour, sheriffs led a young man into courtroom 357 a little after 10 a.m. His case encapsulated the ways meth and trauma can bring someone before the courts.

The man, just 20 years old, wore handcuffs and leg shackles. The laces had been removed from his red skate shoes. He was in mental health court to plead guilty to a series of crimes, some of which related to his crystal meth use.

The man admitted to spitting on a security guard on Oct. 17, 2019, after being hospitalized at the University of Alberta Hospital for a meth overdose. Less than a month later, on Nov. 7, 2019, police arrested him behind the wheel of a stolen Honda Accord after a 10-kilometre, slow-speed chase down the Yellowhead Highway. During the early morning pursuit, the man swerved across multiple lanes, struck guardrails, repeatedly hit the ditch and collided with a police vehicle. He admitted to using meth earlier that day.

Meth was just one factor contributing to the young man’s crimes. His story is marked by displacement and abandonment. He’s been institutionalized throughout his young life and was recently diagnosed with schizophrenia. Lawyer Stephen Brophy told court his client sometimes used meth to self-medicate. For some who find themselves before the courts, meth can be the spark that lights the fuse.

Waking up

For Jocelan Yeomans, who has been recovering from a meth addiction for two years, things entered their endgame in the spring of 2017.

Yeomans and her boyfriend, who was on house arrest, were dealing drugs out of his Meadowlark home. She was in school to become an esthetician. “I remember moving in there thinking we were going to get clean and start a new life,” she said. “I actually was enrolled in school, but that didn’t last.”

One day, Yeomans’ boyfriend got a call from someone who wanted cocaine. She decided to make the run since he wasn’t supposed to leave the home. Months later she got another call, this time on her own cellphone, and made the deal again on her boyfriend’s behalf.

Both times, she had sold to an undercover RCMP officer.

The day Yeomans’ house was raided — March 20, 2017 — she was in the kitchen making dinner, “which was like the first normal thing I ever did in this dysfunctional house,” she said. She heard a banging sound. “I came around the corner and it was the cops. They had a big — I don’t know what you call it — but they took in the door and I had guns in my face, and shields.”

Officers placed her under arrest and hauled her out of the house. “I was beaking off, I was so disrespectful.” On the inside, she was terrified. “I didn’t want to say that at the time, I was trying to be tough.”

Yeomans and her boyfriend were charged with a slew of offences, most of which carried serious jail time. Her initial charge sheet included two counts of trafficking cocaine, possession of meth for the purpose of trafficking, as well as three weapons possession charges and a count for possessing break-in instruments. Yeomans was released from jail three days later. She was eventually arrested twice more as the evidence against her accumulated.

When all was said and done, she faced more than a dozen charges. “I was scared, and I didn’t know what to do,” she said.

Normally, someone in Yeomans’ position would have limited options. She could either take the charges to trial, possibly years in the future, or she could try to plead to whatever the Crown was offering.

Instead, a few things happened in her favour. First, Yeomans’ sister’s husband, who is a lawyer, advised her not to go with her co-accused’s attorney. “He was like … ‘these are some really bad charges Jocelan, you’re going to see your own (lawyer).’”

Yeomans’ lawyer, Stephen Straub, got her to enter guilty pleas to two counts of fraud under $5,000 and a single count of possession of stolen property. She paid restitution.

Straub then applied for Yeomans to go through drug court. At first, she was denied because of the firearms charges. Eventually, she agreed to sign a sworn statement swearing the guns were not hers and that she’d be willing to testify against her co-accused.

“I was 100 per cent honest,” she said.

Yeomans ultimately did not have to testify in the other case. With those charges gone, she was accepted into drug court. She still sees it as something of a miracle.

“Personally, I just know how messed up, and how in denial, and how twisted my reality was,” she said. “And what I was able to justify.”

Read our entire Addicted series on meth in Edmonton:

Addicted Part One: How meth hooked Edmonton — again

Addicted Part Three: How meth takes a toll on Edmonton’s health system and devastates users

Addicted Part Four: How meth erodes Edmonton-area families and communities

Addicted Part Five: How Edmonton could solve its meth problem

Postmedia is committed to maintaining a lively but civil forum for discussion. Please keep comments relevant and respectful. Comments may take up to an hour to appear on the site. You will receive an email if there is a reply to your comment, an update to a thread you follow or if a user you follow comments. Visit our Community Guidelines for more information.