Olympic infrastructure: The good, the bad and the ugly

What Calgary can learn from other host cities

From the friendly atmosphere to heated competition, the 1988 Winter Games left their mark on Calgary.

Not only did the 1988 venues allow Calgary to host, but they made Calgary “the centre of winter sport in Canada,” said GEC Architecture’s David Edmunds, whose firm designed the Saddledome and the Olympic Oval.

“The facilities are a part of the legacy… but the real legacy of those Games was a whole sport training infrastructure in Calgary.”

—David Edmunds, GEC Architecture

Nowadays, the IOC is big on reusing venues wherever possible. Kyle Ripley, head of the city’s bid team, told city council last month that for any new venues, host cities will need to prove their legacy value to the IOC “or that city’s bid will be penalized.”

The IOC is also encouraging host cities to use venues in other cities—and even other provinces. “Using venues outside of Alberta is completely fine,” said Christophe Dubi, Olympic Games executive director.

To justify spending billions of dollars to host the Olympics in 2026, Calgary will need a venue plan that benefits the city, citizens and athletes post-Games.

LESSONS LEARNED

To get a better idea of what a “perfect plan” might look like for 2026, we delved into the history of past Olympics to learn from failures and successes.

1. Montreal: Overdraft

One of the bigger debacles in Olympic infrastructure history was the 1976 Games held in Montreal where the city was slapped with a huge debt totalling $1.5 billion. As reported by the Globe and Mail,“the Big O,” known as “the Big Owe,” cost at least $1.2-billion and took the city 30 years to pay off.

The stadium’s roof was problematic, requiring constant repairs. And when a $37-million fixed roof was finally installed, it tore the next year due to a heavy snow load. The Guardian dubbed the post-Olympic period “the 40-year hangover” for Montreal.

Now the stadium is used mainly for events such as trade shows.

Key takeaway? Remember that the Olympic Games is only a two-week event. You want to get the most out of infrastructure after everyone goes home.

2. Vancouver: Growth

Vancouver 2010 was an example of fruitful infrastructure development. Venues still in use include the Whistler Sliding Centre Luge, Whistler Olympic Park, and the Richmond Olympic Oval. The Luge has been used for athletes in training, recruitment camps, as well as events and competitions.

Vancouver faced some challenges as well. Organizers initially promised to transform the Olympic Village into a mixed-use neighbourhood once the athletes vacated the apartments. The city took on a big financial blow after promising 252 social housing units, but ended up going $46-million over-budget. The city ended up dividing housing between social and market rentals, according to a statement from Mayor Gregor Robertson.

The Village is now thriving, reaching green goals by using solar heating and green roofs. It now offers 1,100 residential units, and also has eateries, bars and retail — giving local businesses space to grow.

3. Rio: Abandonment

The 2016 Games held in Rio were, in many ways, a gong show. So much went wrong. The overall estimated cost for infrastructure was around $12 billion.

The Maracanã Stadium, which underwent major renovations to host the Games, sat dormant after the Olympics and was subject to looting. The stadium closed due to conflicts between stadium operators, the Rio state government and Olympic organizers. Other venues have been closed down and sealed off from public usage.

4. London: Savvy

On a brighter note, one of the finer examples of infrastructure planning is the 2012 London Games. The Athlete’s Village transformed East London providing 2,000 new homes for almost 8,000 people.

The Olympic Stadium continues to bring in high profile events, such as the 2015 Rugby World Cup and the 2017 World Para Athletics Championships.

London also utilized temporary buildings, creating a basketball stadium that was removable. Organizers planned to ship it to Rio for reuse during the 2016 games. Though disassembled in 2013, it was never transported to Rio.

London capitalized on existing architecture, and planned for a future that benefited the city, its people and athletes.

5. Calgary: Durable

The 1988 Games in Calgary put the city on the international map and left a lasting legacy.

The Olympic Oval became the first Olympic site to host indoor speed skating events. It won numerous design awards and serves as a hub for Canada’s national speed skating team, as well as the university community and general public.

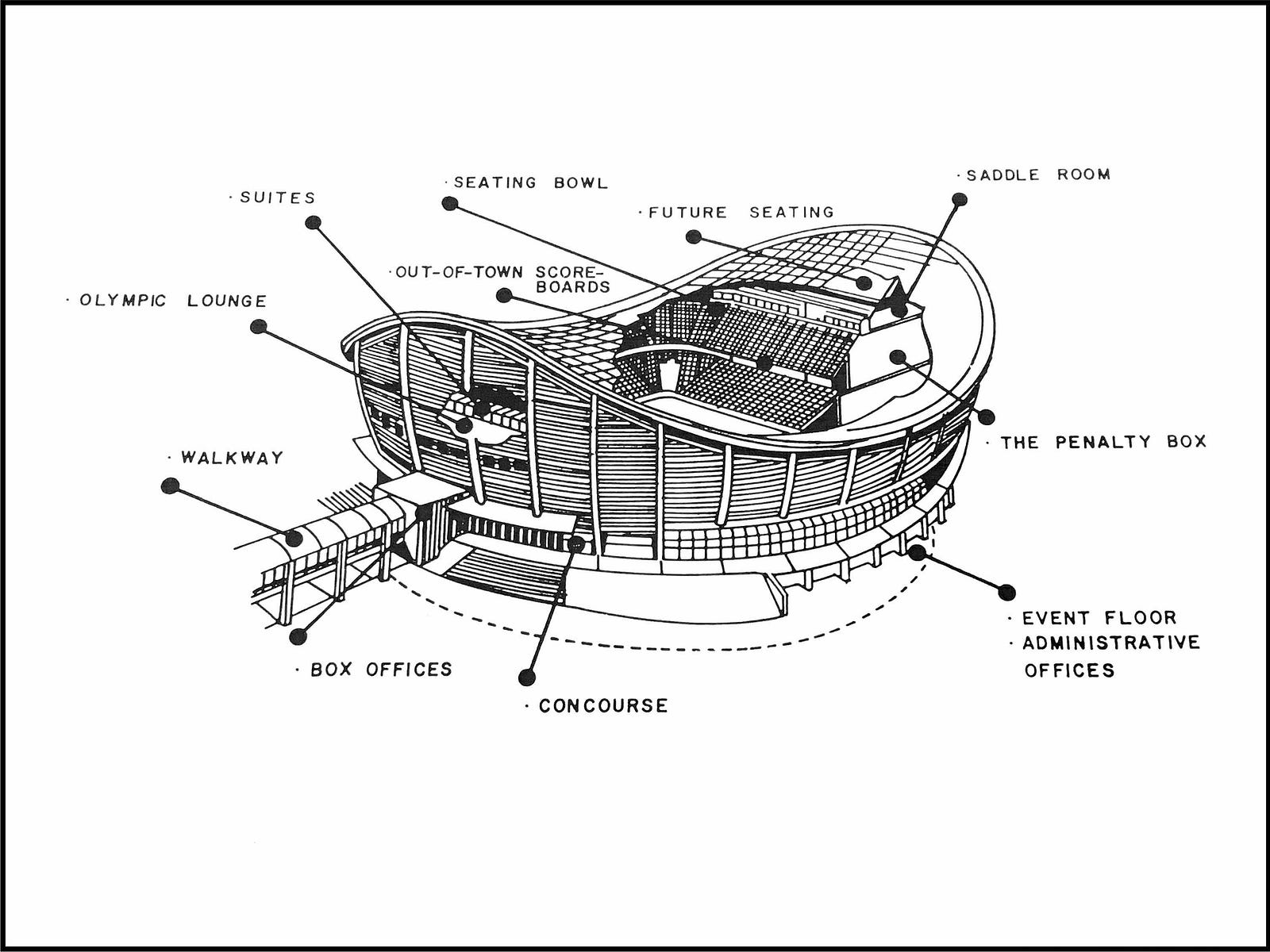

Then there’s the Scotiabank Saddledome, originally called the Olympic Coliseum. It was initially supposed to be a $60-million project. Fast-tracking and structural changes ballooned the cost to $97.7-million, according to the Games’ official report.

The Saddledome’s future is complicated. Even the Calgary firm that designed the Dome, GEC Architecture, acknowledges the obsolescence of the venue.

Calgary also made use of areas outside the city such as Nakiska, which was the alpine skiing site.

“Nakiska wouldn’t exist if the Calgary Olympics didn’t happen,” said Matt Mosteller, spokesperson for the Resorts of the Canadian Rockies (RCR), which owns Nakiska.

In the end, the venues of the ’88 Olympics benefitted Canadian athletes, along with Calgary and its surrounding communities.

“Things were budgeted appropriately and most importantly the facilities that are key to those communities stayed around for future years,” said Mosteller.

The 2026 upgrade price tag

The estimated cost of upgrading existing facilities for 2026 were detailed by the Calgary Olympic bid committee as follows:

- COP ski jumps: $70.7-million

- Olympic Oval: $50.2-million

- WinSport (half-pipe, moguls, aerials): $42.7-million

- Nakiska: $28.6-million

- WinSport sliding facilities (mainly used for bobsleigh and luge): $19.7-million

- Corral Centre (hockey): $18.9-million

- Saddledome (washrooms, electrical and mechanical upgrades): $9.5-million

In total, the bid committee estimated $550-million for venues and facilities—but that number doesn’t include the cost of a new hockey arena.

Rayanne Sabbath, Peter Brand, Miguel Ibe and Lexi Freehill.

This story is part of Hindsight 2026, a joint project between the Sprawl and the Calgary Journal (which is produced by journalism students at Mount Royal University). We’re digging into past Olympics to evaluate whether a 2026 Winter Games in Calgary would help or hinder our city.

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. If you value independent local news, support our work so we can keep digging into municipal issues in the run-up to the 2025 civic election—and beyond!